: zacatecas en el new york times

Luego de irme pasar una temporada a mi pueblo (Zacatecas), con tristeza me doy cuenta de que las cosas ahí se han puesto feas. Muy feas. Además de que nunca ha habido suficientes fuentes de empleo --mi opción en ese lugar para sobrevivir era A) picarme los ojos o B) comer pasto-- y que los migrantes --que aportan el ingreso más importante de capital para el estado con el envío de remesas-- están volviendo a causa de la recesión de EEUU, sin que el estado esté preparado para absorber de pronto tal cantidad de demanda de empleo, ahora hay que sumarle la violencia relacionada al crimen organizado. Lo que alcancé a percibir fue una histeria colectiva detonada por el sitio de terror que la gente de Zacatecas ha comenzado a vivir desde hace no mucho (Jerez es ahora un pueblo fantasma en pleno día, por ejemplo: comercios cerrados, las calles desoladas). Un estado paupérrimo --pero sin indígenas para causar lástima a las conciencias chairas y criollas y al gobierno federal--, un estado antes pacífico y anodino, se enfrenta ahora a un escenario inédito y sombrío. Tan mal pinta el panorama en mi estado, que incluso The New York Times publicó el día 5 de este mes un artículo alarmante al respecto. Para no creerse. Pero así están las cosas en este país, ya con 190 muertes relacionadas con el narco en el 2009, mientras que el monaguillo Felipe Calderón --que funge como presidente, según eso--, durante el Encuentro Mundial de Familias (católicas y biparentales y patriarcales y tradicionales, solamente) aseguró hoy por todos sus santos patronos en un alarde de descarado proselitismo religioso, que gran parte de las víctimas de muerte del crimen organizado han sido provocadas precisamente por la falta de arraigo familiar (sic) y llamó a "proteger a quienes no tienen familia". Como si no ser como ellos lo volviera a uno automáticamente un delincuente. Eso, ni más ni menos, es no tener madre. Ya, que no mame.

The New York Times

January 5, 2009

Kidnappings in Mexico Send Shivers Across Border

By SAM DILLON

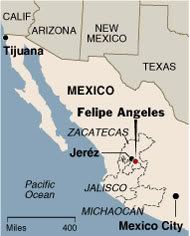

FELIPE ANGELES, Zacatecas, Mexico — Four hooded men smashed in the door to the adobe home of an 80-year-old farmer here in November, handcuffing his frail wrists and driving him to a makeshift jail. They released him after relatives and friends paid a $9,000 ransom, which included his life savings.

The kidnapping was a dismal story of cruelty and heartbreak, familiar all across Mexico, but with a new twist: the daughter of this victim lived in the United States and was able to wire money to help assemble his ransom, the farmer, who insisted that he not be identified by name, said in an interview.

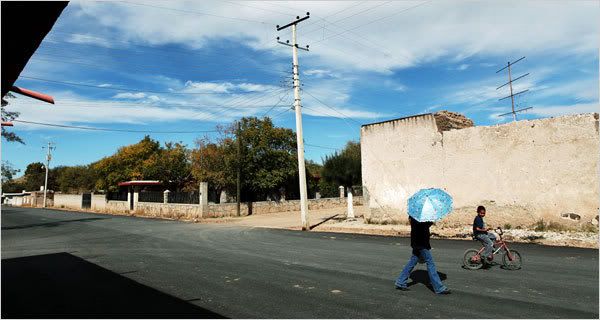

A string of similar kidnappings, singling out people with children or spouses in the United States, so panicked this village in the state of Zacatecas that many people boarded up their homes and headed north, some legally and some not, seeking havens with relatives in California and other American states.

“The relatives of Mexicans in the United States have become a new profit center for Mexico’s crime industry,” said Rodolfo García Zamora, a professor at the Autonomous University of Zacatecas who studies migration trends. “Hundreds of families are emigrating out of fear of kidnap or extortion, and Mexicans in the U.S. are doing everything they can to avoid returning. Instead, they’re getting their relatives out.”

The reported rush into the United States by people from the state of Zacatecas is another sign that Mexico’s growing lawlessness is a volatile new factor affecting the flow of migrant workers across America’s border. The violence is adding a new layer of uncertainty to the always fraught issue of Mexican emigration, already in flux because of the economic downturn in the United States.

Academics and policy makers on both sides of the border, who are watching closely for shifts in migration patterns, say it is too early to know the long-term impact of either the drug-related violence or the loss of jobs by thousands of migrant workers in the United States. But so far, earlier predictions of an exodus of out-of-work Mexicans back to their hometowns seem to have been premature.

Instead, it appears that the pattern in the state of Zacatecas — where many people have family in the United States — may be a good indicator of what is happening throughout Mexico. The country’s spiraling criminality appears not only to be keeping some Mexicans in the United States, but it may also be leading more Mexicans to flee their country. “It’s a toxic combination right now,” said Denise Dresser, a political scientist based in Mexico City.

Mexicans north of the border are facing joblessness and persecution, but in their own country the government can’t provide basic security for many of its citizens.”

The extraordinary increase in violence in Mexico in recent years has resulted in part from President Felipe Calderón’s war against drug lords. His campaign to arrest the leaders of the cartels and the military officers and law enforcement officials they have compromised has unleashed factional fighting among rival drug groups, as well as violence against the government.

Traditionally, most of Mexico’s criminal violence has been concentrated in northern border cities like Tijuana where cocaine enters the United States. But law and order have been deteriorating in many regions; and heartland states like Michoacán, Jalisco and Zacatecas, which are the homes of millions of migrants to the United States and are longtime drug smuggling routes, are now also reporting spikes in killings and kidnappings.

Jerez, a town of 60,000 a few miles northwest of Felipe Angeles in Zacatecas, was until recently a calm place, largely untouched by organized crime, said Abel Márquez Haro, a grocery wholesaler. [Leer el artículo completo en el New York Times].