: árboles de humo

Estoy muy impresionado leyendo la penúltima novela de Denis Johnson (Munich, 1949), el antes famoso "secreto mejor guardado de la literatura norteamericana" en estos días sin internet en los que de pronto me rinde más el tiempo. Es contundente y demoledor. Échenle un ojo.

By JIM LEWIS

Good morning and please listen to me: Denis Johnson is a true American artist, and “Tree of Smoke” is a tremendous book, a strange entertainment, very long but very fast, a great whirly ride that starts out sad and gets sadder and sadder, loops unpredictably out and around, and then lurches down so suddenly at the very end that it will make your stomach flop. It comes with the armor and accoutrements of a Major Novel: big historical theme (Vietnam), semi-mythical cultural institution (military intelligence), long time span (1963-70, with a coda set in 1983) and unreasonable length (614 pages), all of which would be off-putting if this were not, in fact, a major novel, and if Johnson’s last big book hadn’t been the small collection of eccentric and addictive short stories called “Jesus’ Son” (1992). “Tree of Smoke” is a soulful book, even a numinous one (it’s dedicated “Again for H.P.” and I’ll bet you a bundle that stands for “higher power”), and it ought to secure Johnson’s status as a revelator for this still new century — a prediction I voice confidently but reluctantly, and with a little disappointment and dismay.

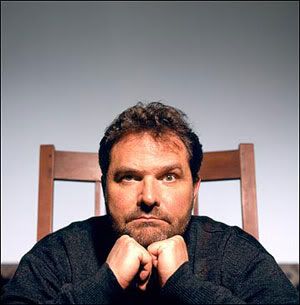

Reluctantly, because Johnson has always been an elusive figure, one of the last of the marginal masters. He’s not a recluse, but he’s not out humping his ego, either: I’ve never read an interview with him (though I haven’t looked very hard), or seen a picture of him that wasn’t on one of his book jackets. More important, it has often seemed as if the books themselves — there have been six novels, a book of short stories and one of plays, three volumes of poetry and a collection of journalism — have bloomed spontaneously from the secret fissures that crisscross Americana: jail cells, bad neighborhoods, bus stations, cheap frame houses in the fields beyond the last streetlight. They’re full of deprived souls in monstrous situations, hapless pilgrims on their way to their next disaster. But unlike most books about the dispossessed, they’re original (how strange it feels to use that word these days, but it fits), and what’s more, deliriously beautiful — ravishing, painful; as desolate as Dostoyevsky, as passionate and terrifying as Edgar Allan Poe.